Greetings from London. I’m here for a short visit, weaving together a meeting with the LifeArc Early Ventures team, an afternoon with the leadership of Closed Loop Medicine, and some time with friends. On Sunday, I caught the last night of the London Jazz Festival, and an unusual duo performance of Bill Laurance and Michael League of Snarky Puppy.

Heading back to the US this afternoon for Thanksgiving tomorrow with my family at Chief O’Neill’s in Chicago, and in the spirit of the week, I’ve been remembering and appreciating the people who, at a distance, influenced my career. Here’s a story about an important one of them. Happy Thanksgiving! →

Startups are bands, yet we don’t often ask founders about their influences. I’ve been reflecting on mine recently and how they shaped me. One of the earliest and most important was artist and engineer Beatriz da Costa who indirectly nudged my professional life in a new direction many years ago. I wish she was still alive so I could thank her for that.

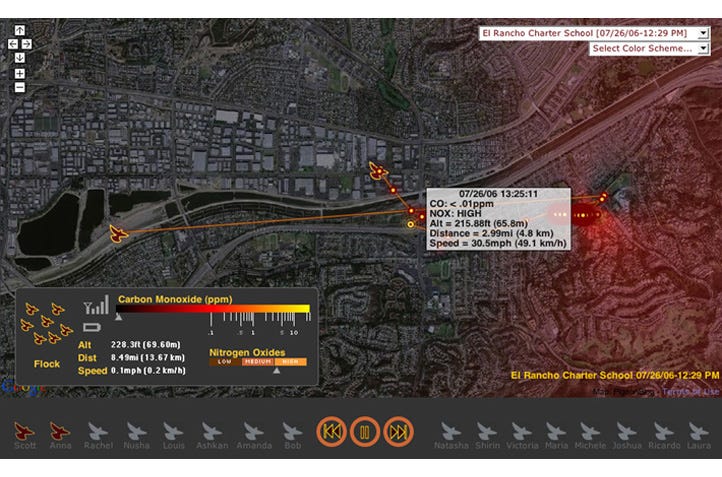

Da Costa is best known as the person behind an unlikely project in 2006 that outfitted a flock of homing pigeons with tiny backpacks, filled with small equipment that would measure and report air pollution as they flew home to their coops through miles of city.

She called it PigeonBlog, as though the birds were posting about the air quality as they traveled. Inspired by a historical photograph of a pigeon with a camera around its neck, ready for wartime duty, she saw the potential for recruiting the birds a hundred years later as partners in understanding and calling attention to the environment.

It was, in many ways, a ridiculous and laughable electronic art project. It was also a momentous breakthrough - proof, more than a year before the first iPhone was released, that cell phone components (eg, GPS/GSM modules) could be used to connect objects in the world to the network, and that the information from them could be made immediately available and useful on the internet.

Her work created a powerful new vector in technology. These were the first signs of social, networked objects that would become ubiquitous years later.

Her artwork declared we already had in hand the tools and materials needed to start building previously impossible things. We were only limited by our imagination. In mine, she illuminated a path to chasing asthma in the wild. I realized if it was possible to do this with pigeons, so too would it be with medicines. Soon after, I started adding electronics to inhalers and creating real-time maps of asthma symptoms in the community. Asthmap — later, Asthmapolis, and then still later, Propeller — was born.

Da Costa and her peers were combining art and technology to make platforms for annotating the world. By inventing new ways to collect and convey information, they saw a way one could interest people again. Often they were just reintroducing us to ordinary things we had not noticed or had grown bored of.

Occasionally this took the form of grassroots citizen science. Da Costa used her art to spark imagination and interest in things that mattered, like poor air quality, but with which we had stopped bothering.

In this case, she built PigeonBlog out of holes she found in science. Twenty years ago, one could assume that all the interesting questions about air quality had been asked and answered. Cities had scattered networks of fixed, costly, sophisticated monitoring stations. To get an estimate for somewhere in between, you used math and an interpellation model.

Da Costa appreciated, when few others did, exactly how much this approach assumed. She realized that measurements by the birds had the potential of validating, or challenging, these dispersion models and might make us aware of other things we weren’t seeing.

Hers was the first three-dimensional view of air quality, for example. Monitors on the ground couldn’t tell you what was happening hundreds of feet up, where the birds flew and traffic-related pollution was mixing and drifting.

And while monitors were generally positioned in quiet, low-traffic areas rather than known pollution hotspots (to obtain more representative values), pigeons tend to fly by means of visual cues such as highways and landmarks. Measuring air quality along these common routes, could yield more accurate estimates of actual exposures to residents of the area.

The project made scientific sense, but she never really meant for it to be about that. Instead, she told the NY Times, it was “a way of generating attention, a way of disturbing things.” Or, as Alain de Botton recently put it, “We don’t need to make art in order to learn the most valuable lesson of artists, which is about noticing properly, living with our eyes open and thereby, along the way, savoring time.”

Da Costa’s work challenged and surprised, but it also divided the audience. The media wasn’t sure what to make of PigeonBlog, or of university art faculty doing research - or was it activism? She was uniquely qualified to capture our attention, but her scientific qualifications and credibility were challenged. PETA accused her of animal abuse. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology asked her to join a board of directors. She was approached by DARPA about converting the technology into a defense instrument. In her artist statement, she talks through the disorienting and unexpected support and criticism she received.

Thankfully she kept going, as though the only thing that mattered was how many people appreciated her work, not the number that didn’t. She knew you only needed a few people to start to believe to get something going.

Da Costa was one of those creative people who work in the open with others so effectively they basically create a scene: she joined the Critical Art Ensemble, co-founded another group called Preemptive Media, and worked at Eyebeam Art and Technology Center.

She was, in fact, astonishingly prolific. It is difficult to summarize how much she produced. Like Werner Herzog, she just never stopped making stuff. On her own she created projects like Molecular Invasion, Free Range Grains, and GenTerra. With others, she made projects like Zapped, Swipe, and Air, a participatory air quality monitoring community that helped inspire the work Propeller would later do with the city of Louisville.

She always appeared to be working, but watch a few videos of her projects and you get the sense that it feels like play to her. That seems like a valuable secret to relearn from her. Aim to create and work on more projects in the spirit of fun.

She died just a few years after PigeonBlog, from a recurrence of cancer, for which she had been treated several times as a teenager and young adult. Right up until her death, she was making projects the drew us into the difficult aspects of life with cancer, and its research and treatment, like The Cost of Life, The Endangered Species Finder, Memorial for the Still Living, The Life Garden, Dying for the Other, The Delicious Apothecary and The Anti-Cancer Survival Kit.

There was always something urgent in her art and imagination. It showed us new ways to notice the world, to be curious and healthy in it, to be connected to each other and to our communities and places, and to live in that state of wellbeing as long as we can. Her projects lead us to the mystery and truths that come from the interaction of nature and art, of facts and imagination. And she taught us to surround ourselves with people who make and notice things with energy as part of their daily life, and to try to be one yourself. 🙏

David,

Thank you so very much for sharing this story. In today's busy world, it's common to get stuck in cruise control and forget to look around. I really value your perspective shared on the role of the artist 'noticing properly, living with eyes open, and savoring time.' All entrepreneurs and problem solvers can learn from Da Costa.

-Ashley