Entrepreneurs are taught to put willingness-to-pay at the core of their product designs and business models. That training sends many healthtech companies to the health economics literature to try to learn how people would value a treatment or intervention.

We did this in the early days at Propeller.

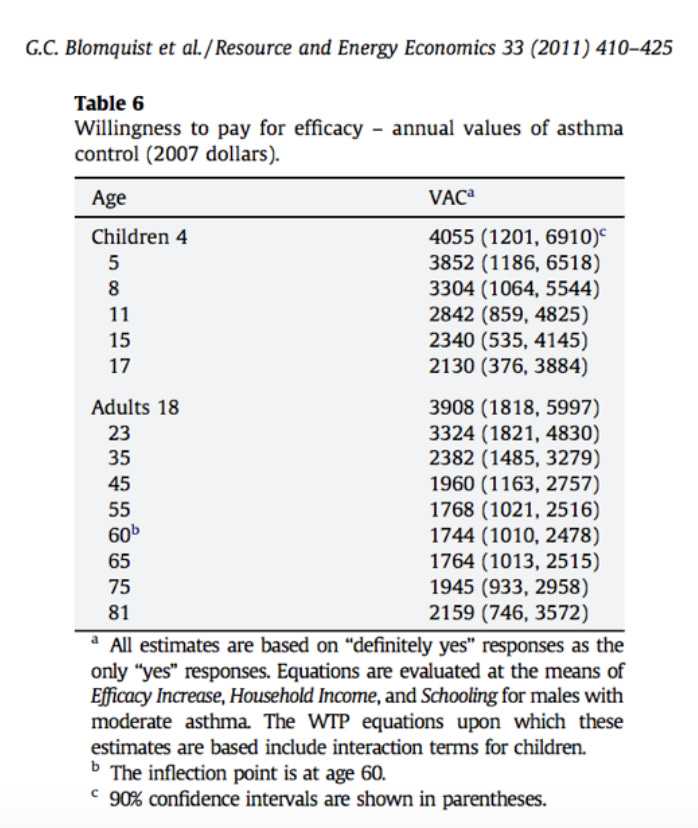

The studies seemed promising, possibly perfect. When interviewed, people with asthma in one study reported willingness-to-pay $10-11 to avoid a single day with symptoms, and $20-24 to avoid a day with more significant effects. In another case, the sums were even higher: $36-47 per day of symptoms avoided and $67-89 per bad symptom day. One study demonstrated a similarly high value for annual asthma control.

It all made sense. Asthma attacks can be sudden, frightening, even life-threatening. You expect people with asthma to be strongly motivated to eliminate those moments and reduce that suffering. Add the extra household expenses and hard social costs (eg missed school and work) from poorly controlled asthma, and it seemed obvious.

As a young company, you can build a business model around those numbers. The financial model will sing. It will have academic rigor. Your technology team will think you found a secret window on how people will react to your product in the future. We dedicated an entire slide to it in an early pitch deck.

It completely broke apart when it met the market.

The cracks opened immediately. Slower than expected enrollment in an early clinical trial. It is harder than it should be to get someone to use something that they say they want.

We watched our competitors make the same mistake. Consumer campaigns quickly stumbled and were shut down. We tried to warn newcomers because it seemed worse for everyone if DTC launch after launch ended in disappointment.

The history of respiratory digital health has basically been a repeating sequence of companies developing technology that promised improved management of disease, and then trying and failing to sell it to consumers. It’s been true of medication trackers, spirometers and peak flow meters, lung sound recorders, exhaled breath analyzers, and respiratory rate quantifiers.

Too many of us convinced ourselves the academic studies showed people would behave rationally. We took willingness-to-pay data as evidence to build logical products, which no one wanted to buy. We didn’t believe it was possible for those solutions to fail, because they made so much sense they could not possibly be wrong.

You can’t blame the health economists. If you dig deeper, the warnings are there. High rates of risk tolerance, significant discounting of future outcomes, the probability of adherence near zero. Oof.

Once we started paying attention to the real reasons behind people’s behavior, and stopped trying to focus on the ostensibly logical ones, we made much better business decisions. We had to regularly stop pretending adoption (or engagement) was more logical than it really was. We could never unravel the conundrum, but at least we knew it was there and could step around it.

Trouble is, I still hear too many founders and big company executives making plans for product and business designs heavy on logic and light on magic. That assume consumers make dominantly rational choices about adopting and using digital health products.

As an industry, we have an understandable need to appear scientific in our methodology. We use data and health economic evidence to design products and businesses because we want to be taken seriously by traditional actors and institutions preoccupied with logic. What bothers me is how often this prevents us from considering other, less logical and more magical solutions.

The person who has the most to teach digital health at the moment is Rory Sutherland, an advertising executive who wrote a book called Alchemy. Effectively, a hilarious manual for when and how to abandon logic. As he sees it, “problems almost always have a plethora of seemingly irrational solutions waiting to be discovered, but nobody is looking for them.”

Which is how we’ve ended up making the same mistake in respiratory health for the last twenty years, failing to spot when we’re involved with things where the laws of logic do not apply. I’m advocating for more digital health that follows Sutherland’s mantra: “Test counterintuitive things, because no one else ever does.”

I love these thoughts. It's hard to advocate for magic over logic internally, but the truly special things are more magic than logic, as you say.

I have NEVER been a fan of willingness to pay models. Heavily dependent or whether it is your money or somebody elses money-- and to me never really translated into what happens in the real world- as David nicely pointed out. Also a huge disconnect between what a person perceives as being important now vs. weeks or months from now!