Revisiting What We Missed in Landmark Epidemiological Studies

Hunting for overlooked insights in their findings and datasets with the latest AI tools

The 1990s and early 2000s were the heyday of large epidemiological studies. These projects were Herculean expeditions: vast, long-term, multi-country efforts that collected data from millions of people under a common protocol.

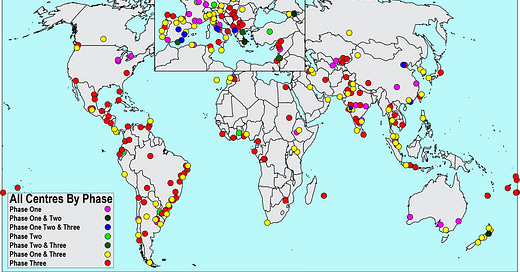

At the top of the list—truly, it has a Guinness Record—is ISAAC, the International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood, which launched in 1991, and by its conclusion in 2005, had involved more than 2M children from more than 100 countries.

Some of the most well-known advances in understanding asthma origins and prevalence, such as the hygiene hypothesis, emerged from its efforts. But we no longer explore cross-cultural variation in the origins of chronic disease with the same energy, and the world has also grown more interconnected in the last two decades. These studies and their warehouses of data capture important variability in exposure that often no longer exists.

ISAAC has a website that curates the history of the project, including interviews and personal reflections with its investigators, summaries of its methods and main results, and citations to its 500+ published papers.

Reading the history, I wondered what we might learn by re-examining the data collected by ISAAC using the new AI tools we now have at hand. Over the past week, I pointed o1 pro at the site and its accumulated publications and reports, and asked it to revisit ISAAC and explore the project for overlooked insights.

Granted ChatGPT could only access a fraction of the published papers, and none of the raw participant or center-level datasets or detailed statistical outputs. Nor did I give it an ability to explore other, relevant + complementary data that might exist elsewhere.

I asked the model to report its findings in the form of a research letter for a journal, limiting itself to 1,200 words on the most interesting observations. After a few rounds of feedback and editing, I had a workable manuscript, highlighting several surprising inconsistencies and mismatches, which I’ve submitted to a respiratory journal (with appropriate disclosures).

Before the datasets and project archives from ISAAC are lost to time, re-analyses using new analytical tools could be a worthwhile way to uncover productive new clues about asthma, especially for a team with access to underlying data.

Other landmark studies warrant similar attempts. For example, projects like MONICA, which explored cardiovascular disease in 10 million people from 20+ countries, and EPIC, which studied cancer and chronic diseases in relation to dietary, lifestyle, and environmental factors among >500k participants from 10 European countries. And unexpectedly, I’ve recently seen news that datasets like YRBSS and others are being taken offline and made inaccessible to the public. Those study databases and others like NHANES, may be worth exploring, too, before they fade or are pushed into obscurity.